The eventful history of the Speicherstadt began in the 19th century.

Today, 140 years later, the world-famous historical warehouse district is much more than just a monument. Future capital is piled up on stylishly restored floors.

Everyone thinks they know it, but it always has plenty of new surprises in store: the Speicherstadt historical warehouse district. Opened in 1888, the coherent red-brick ensemble that stretches for miles is a hit with tourists visiting Hamburg from all over the world. They stroll along the canal through Hanseatic history and yet encounter the future on every corner. That’s because the sympathetically renovated and converted Speicherstadt is now also a magnet for creatives, company founders, start-ups and future technologies. There is the ‘Digital Hub Logistics’, for example, where young companies with innovative business models for port logistics converge. The start-up ‘Wildplastic’ is committed to establishing a circular economy that preserves resources by recovering plastic waste. This is processed into granules and then transformed into new plastic products. Just a short walk away is the company ‘Stadt Land Frucht’, which supplies the offices in the surrounding districts with fresh and healthy organic snacks. And Block H on Sandtorkai is currently even being converted into a ‘climate-friendly storage block’: with specially developed high-tech solutions, energy experts are exploring how the entire Speicherstadt could one day be supplied with carbon-neutral energy.

A favourite among entrepreneurs: More and more innovative spirits, start-ups and their backers are drawn to the spaces with warehouse flair.

A vibrant cultural heritage

In 2015, UNESCO, the cultural organisation of the United Nations, declared the Speicherstadt historical warehouse district a World Heritage Site, together with the neighbouring Kontorhaus district and the Chilehaus, taking the listed status awarded in 1991 to a new level as a testament to a building culture worthy of preservation. The container, which began changing the face of logistics at the end of the 1960s, had long since replaced the warehouse blocks as a storage location. The metal box itself became the warehouse. Only certain types of goods, carpets in particular, are still stored and traded in the Speicherstadt to this day. The district had otherwise already lost its old function and yet was by no means just standing there with no purpose. The old, magnificent warehouses were far too coveted for that to happen. As landlords and managers of the Speicherstadt, HHLA’s real estate specialists have been finding new, modern and groundbreaking uses for it since 1994. Thanks to the full-scale renovations and clever redesign, completely new tenants have now moved in next to the remaining trading companies. At first, museums and leisure attractions such as Miniatur Wunderland, with the biggest HO scale model railway in the world, or the Hamburg Dungeon delighted new visitors. Then came fashion and advertising agencies, followed by a growing number of companies from the start-up ecosystem.

Innovative system: The optimal heat transfer mixing ratio for the storage block’s energy system is managed at the central distribution point – supported by the ice storage tanks in the basement.

Finding flexible solutions

The sympathetic development of the venerable Speicherstadt is always setting its sights on new goals. A glass bridge was built to enable Germany’s most visited museum, Miniatur Wunderland, to continue to grow. It links the original exhibition space with the extension on the other side of the Kehrwieder canal, providing a nice example of the Speicherstadt’s ability to transform and make connections. Not far away, in the Kontorhaus on Pickhuben, construction specialists from universities are working with experts from HHLA Real Estate to research into a ‘climate-friendly storage block’ that is attracting attention across Europe. They are investigating how it might not only be possible, but also economically attractive to carry out an energy-efficient renovation of existing properties under the strict conditions governing listed buildings on the UNESCO World Heritage Site. As soon as the combination of innovative solar tiles and cutting-edge heat storage media is ready for mass production, the model can lead the way for the energy-efficient conversion of commercial properties throughout Germany – and beyond.

93 %

of the heat needed could be generated by the storage blocks themselves.

A child of the customs union

Without Hamburg’s accession to the German Empire’s custom union in October 1888 the Speicherstadt mega construction project would not have been necessary at all. But to compensate for the fact that Hamburg was set to lose its privilege as a free trade city, the Hanseatic city wrested a ‘free port’ from the Empire government. In this separate part of the port, goods could still be handled and stored without any customs controls. The traditional office buildings along the canals in the city centre were outside this zone, so warehouses had to be built in the area of the new free port. To this end, the Norddeutsche Bank founded a public limited company in 1885 at the request of the Senate: the Hamburger Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft (HFLG), now known as HHLA. The Hanseatic city retained a vital, regulatory influence within this construct.

However, a huge obstacle stood in the way of the so-called ‘customs union buildings’. The designated site was already occupied by densely populated residential areas where around 17,500 people lived – predominantly middle class in the Wandrahm district, while the people in the Gänge district on the Kehrwieder lived in cramped conditions and often in extreme poverty. This did not prevent the planners from presenting it as a fait accompli. Within 24 months, more than 1,000 residential buildings were demolished without the city allocating new housing to the people who lived in them. The main section of the Speicherstadt had to be completed by autumn 1888, and the planners adhered to the tight schedule. On 29 October, Kaiser Wilhelm II laid the keystone, ceremoniously marking Hamburg’s accession to the German Customs Union. Extending over a total area of some ten square kilometres, the newly built free port was now considered the biggest in the world.

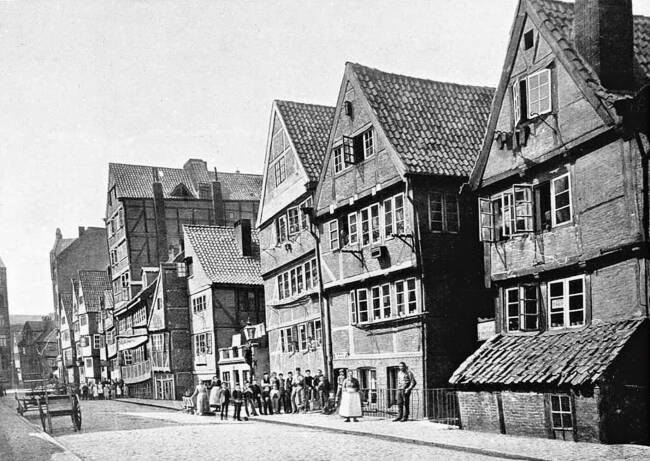

Old houses on Brooksgraben: They were demolished from 1883 onwards to make room for the free port and the Speicherstadt. There were about 1,100 houses in the Kehrwieder and Wandrahm districts, which were home to 17,500 people.

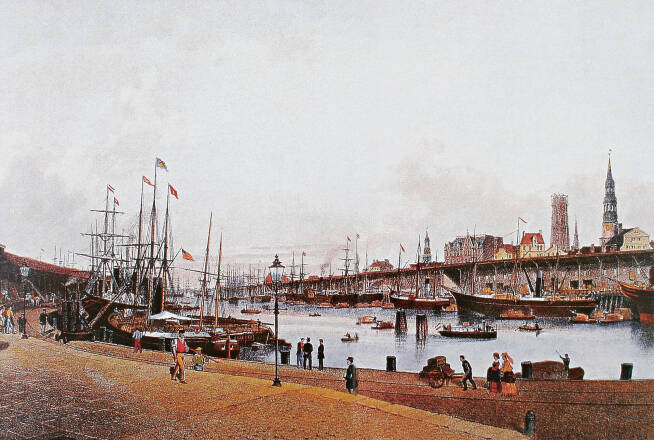

Sandtorhafen is a harbour where steamships and cargo sailing boats docked. It was built in 1866 and considered revolutionary because the ships were readied on the quay. Back then, barges usually brought the cargo along the Elbe, where it was dropped in the stream of the freighters.

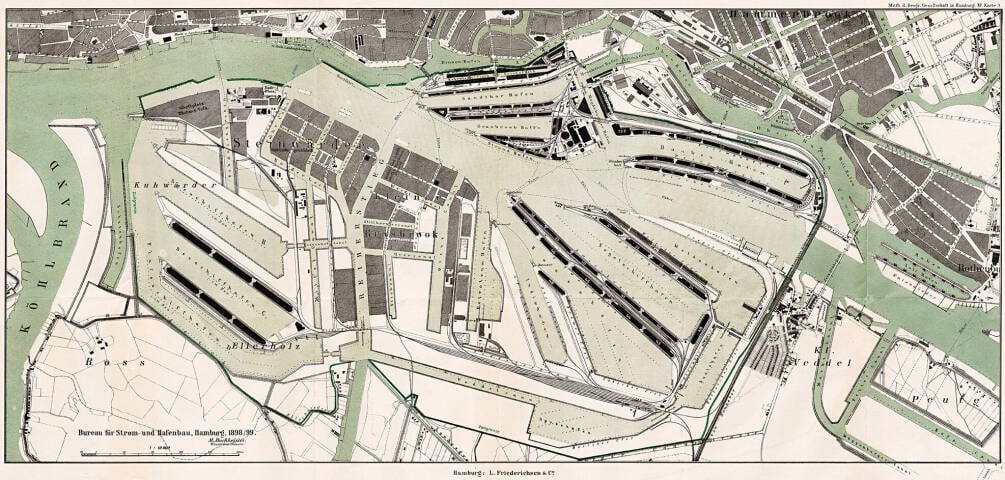

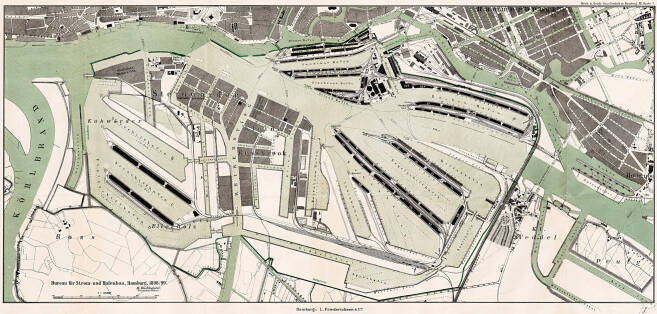

Huge free port: The Free Port of Hamburg built in 1888 was the biggest in the world, extending over an area of 10 km². Those who put down roots here could take advantage of discounted imports when trading with the German Empire.

For the keystone laying ceremony on 29 October 1888, most Hamburg residents were given time off work or school to hail Kaiser Wilhelm II. Here, the dignitaries await his arrival by the decorated Brooks Bridge to inaugurate the first construction phase of the new Speicherstadt.

17,500 people were forced to leave their homes.

Cathedrals of work

The red-brick buildings built on thousands of piles were not only functional, but also an expression of the Hamburg merchants’ pride. The planners and builders around the chief engineer of the building committee, Franz Andreas Meyer, were influenced by the ‘Hanoverian school of architecture’ and the sacred North German Brick Gothic. A crown jewel of the Speicherstadt is the ‘town hall’, which was inaugurated in 1904. The headquarters of the HHLA Group came up with this name because its cornices, oriels and decorative elements looked almost palatial. ‘Bei St. Annen 1’ was joined to the adjacent warehouses in 2001/2002 by the award-winning architectural practice gmp (von Gerkan, Marg and Partners). They combined modern offices, meeting rooms and lifts with historic beams and staircases. Since the conversion, a striking glass roof curves over the formerly open atrium.

For more than 120 years, the ever-growing HHLA has been managed from the majestic administrative building overlooking by the canal.

Ultra-modern from the outset

From the very start, the newly built Speicherstadt was nothing less than the biggest and most modern port logistics centre of its time. Even then, it was multimodal, meaning it was designed for various carriers. Particularly important was the good link to the adjacent harbour known as Sandtorhafen. Rails ran through the complex, there were many good streets for horse-drawn carts and later lorries, while barges were able to moor on the waterside of the canal, where they were unloaded with hydraulic cranes and winches. There were lifts and pneumatic tube systems, and even the still relatively uncommon electric light had been installed everywhere. A specially built power plant supplied the entire complex with electricity.

Customs boundary: Fences and barriers separated the duty-free Speicherstadt (here in the 1930s) from the city of Hamburg.

300,000

square metres of space are now rented out by HHLA in the Speicherstadt.

Coffee exchange and tea traders

The red-brick buildings built on thousands of piles were not only functional, but also an expression of the Hamburg merchants’ pride. The planners and builders around the chief engineer of the building committee, Franz Andreas Meyer, were influenced by the ‘Hanoverian school of architecture’ and the sacred North German Brick Gothic. A crown jewel of the Speicherstadt is the ‘town hall’, which was inaugurated in 1904. The headquarters of the HHLA Group came up with this name because its cornices, oriels and decorative elements looked almost palatial. ‘Bei St. Annen 1’ was joined to the adjacent warehouses in 2001/2002 by the award-winning architectural practice gmp (von Gerkan, Marg and Partners). They combined modern offices, meeting rooms and lifts with historic beams and staircases. Since the conversion, a striking glass roof curves over the formerly open atrium.

Hälssen and Lyon moved into an office and warehouse building in 1887, which remains the headquarters of the famous tea company to this day.

Quartiersleute

then and now

read more

Hamburger Hafen und Logistik Aktiengesellschaft

Bei St. Annen 1

20457 Hamburg

Phone +49 40 3088-0

www.hhla.de/en

Responsible in terms of the German press law

Carolin Flemming, Head of Corporate Communications

→ Write e-mail

Photo credits

Adobe Stock, hamburger-fotoarchiv.de, Thomas Hampel, Hälssen & Lyon / Zitzlaff, HHLA, Georg Koppmann, Archiv Egbert Kossak, Nele Martensen, Thies Rätzke, Gustav Werbeck, Wikipedia

Editor in chief

Christian Lorenz

The eventful history of the Speicherstadt began in the 19th century. Today, 140 years later, the world-famous historical warehouse district is much more than just a monument. Future capital is piled up on stylishly restored floors.

Everyone thinks they know it, but it always has plenty of new surprises in store: the Speicherstadt historical warehouse district. Opened in 1888, the coherent red-brick ensemble that stretches for miles is a hit with tourists visiting Hamburg from all over the world. They stroll along the canal through Hanseatic history and yet encounter the future on every corner. That’s because the sympathetically renovated and converted Speicherstadt is now also a magnet for creatives, company founders, start-ups and future technologies. There is the ‘Digital Hub Logistics’, for example, where young companies with innovative business models for port logistics converge. The start-up ‘Wildplastic’ is committed to establishing a circular economy that preserves resources by recovering plastic waste. This is processed into granules and then transformed into new plastic products. Just a short walk away is the company ‘Stadt Land Frucht’, which supplies the offices in the surrounding districts with fresh and healthy organic snacks. And Block H on Sandtorkai is currently even being converted into a ‘climate-friendly storage block’: with specially developed high-tech solutions, energy experts are exploring how the entire Speicherstadt could one day be supplied with carbon-neutral energy.

A favourite among entrepreneurs: More and more innovative spirits, start-ups and their backers are drawn to the spaces with warehouse flair.

Lebendiges Kulturerbe

In 2015, UNESCO, the cultural organisation of the United Nations, declared the Speicherstadt historical warehouse district a World Heritage Site, together with the neighbouring Kontorhaus district and the Chilehaus, taking the listed status awarded in 1991 to a new level as a testament to a building culture worthy of preservation. The container, which began changing the face of logistics at the end of the 1960s, had long since replaced the warehouse blocks as a storage location. The metal box itself became the warehouse. Only certain types of goods, carpets in particular, are still stored and traded in the Speicherstadt to this day. The district had otherwise already lost its old function and yet was by no means just standing there with no purpose. The old, magnificent warehouses were far too coveted for that to happen. As landlords and managers of the Speicherstadt, HHLA’s real estate specialists have been finding new, modern and groundbreaking uses for it since 1994. Thanks to the full-scale renovations and clever redesign, completely new tenants have now moved in next to the remaining trading companies. At first, museums and leisure attractions such as Miniatur Wunderland, with the biggest HO scale model railway in the world, or the Hamburg Dungeon delighted new visitors. Then came fashion and advertising agencies, followed by a growing number of companies from the start-up ecosystem.

Innovative system: The optimal heat transfer mixing ratio for the storage block’s energy system is managed at the central distribution point – supported by the ice storage tanks in the basement.

Finding flexible solutions

The sympathetic development of the venerable Speicherstadt is always setting its sights on new goals. A glass bridge was built to enable Germany’s most visited museum, Miniatur Wunderland, to continue to grow. It links the original exhibition space with the extension on the other side of the Kehrwieder canal, providing a nice example of the Speicherstadt’s ability to transform and make connections. Not far away, in the Kontorhaus on Pickhuben, construction specialists from universities are working with experts from HHLA Real Estate to research into a ‘climate-friendly storage block’ that is attracting attention across Europe. They are investigating how it might not only be possible, but also economically attractive to carry out an energy-efficient renovation of existing properties under the strict conditions governing listed buildings on the UNESCO World Heritage Site. As soon as the combination of innovative solar tiles and cutting-edge heat storage media is ready for mass production, the model can lead the way for the energy-efficient conversion of commercial properties throughout Germany – and beyond.

93 %

of the heat needed could be generated by the storage blocks themselves.

A child of the customs union

Without Hamburg’s accession to the German Empire’s custom union in October 1888 the Speicherstadt mega construction project would not have been necessary at all. But to compensate for the fact that Hamburg was set to lose its privilege as a free trade city, the Hanseatic city wrested a ‘free port’ from the Empire government. In this separate part of the port, goods could still be handled and stored without any customs controls. The traditional office buildings along the canals in the city centre were outside this zone, so warehouses had to be built in the area of the new free port. To this end, the Norddeutsche Bank founded a public limited company in 1885 at the request of the Senate: the Hamburger Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft (HFLG), now known as HHLA. The Hanseatic city retained a vital, regulatory influence within this construct.

However, a huge obstacle stood in the way of the so-called ‘customs union buildings’. The designated site was already occupied by densely populated residential areas where around 17,500 people lived – predominantly middle class in the Wandrahm district, while the people in the Gänge district on the Kehrwieder lived in cramped conditions and often in extreme poverty. This did not prevent the planners from presenting it as a fait accompli. Within 24 months, more than 1,000 residential buildings were demolished without the city allocating new housing to the people who lived in them. The main section of the Speicherstadt had to be completed by autumn 1888, and the planners adhered to the tight schedule. On 29 October, Kaiser Wilhelm II laid the keystone, ceremoniously marking Hamburg’s accession to the German Customs Union. Extending over a total area of some ten square kilometres, the newly built free port was now considered the biggest in the world.

Old houses on Brooksgraben: They were demolished from 1883 onwards to make room for the free port and the Speicherstadt. There were about 1,100 houses in the Kehrwieder and Wandrahm districts, which were home to 17,500 people.

Sandtorhafen is a harbour where steamships and cargo sailing boats docked. It was built in 1866 and considered revolutionary because the ships were readied on the quay. Back then, barges usually brought the cargo along the Elbe, where it was dropped in the stream of the freighters.

Huge free port: The Free Port of Hamburg built in 1888 was the biggest in the world, extending over an area of 10 km². Those who put down roots here could take advantage of discounted imports when trading with the German Empire.

For the keystone laying ceremony on 29 October 1888, most Hamburg residents were given time off work or school to hail Kaiser Wilhelm II. Here, the dignitaries await his arrival by the decorated Brooks Bridge to inaugurate the first construction phase of the new Speicherstadt.

17,500 people were forced to leave their homes.

Cathedrals of work

The red-brick buildings built on thousands of piles were not only functional, but also an expression of the Hamburg merchants’ pride. The planners and builders around the chief engineer of the building committee, Franz Andreas Meyer, were influenced by the ‘Hanoverian school of architecture’ and the sacred North German Brick Gothic. A crown jewel of the Speicherstadt is the ‘town hall’, which was inaugurated in 1904. The headquarters of the HHLA Group came up with this name because its cornices, oriels and decorative elements looked almost palatial. ‘Bei St. Annen 1’ was joined to the adjacent warehouses in 2001/2002 by the award-winning architectural practice gmp (von Gerkan, Marg and Partners). They combined modern offices, meeting rooms and lifts with historic beams and staircases. Since the conversion, a striking glass roof curves over the formerly open atrium.

For more than 120 years, the ever-growing HHLA has been managed from the majestic administrative building overlooking by the canal.

Ultra-modern from the outset

From the very start, the newly built Speicherstadt was nothing less than the biggest and most modern port logistics centre of its time. Even then, it was multimodal, meaning it was designed for various carriers. Particularly important was the good link to the adjacent harbour known as Sandtorhafen. Rails ran through the complex, there were many good streets for horse-drawn carts and later lorries, while barges were able to moor on the waterside of the canal, where they were unloaded with hydraulic cranes and winches. There were lifts and pneumatic tube systems, and even the still relatively uncommon electric light had been installed everywhere. A specially built power plant supplied the entire complex with electricity.

Customs boundary: Fences and barriers separated the duty-free Speicherstadt (here in the 1930s) from the city of Hamburg.

Coffee exchange and tea traders

The red-brick buildings built on thousands of piles were not only functional, but also an expression of the Hamburg merchants’ pride. The planners and builders around the chief engineer of the building committee, Franz Andreas Meyer, were influenced by the ‘Hanoverian school of architecture’ and the sacred North German Brick Gothic. A crown jewel of the Speicherstadt is the ‘town hall’, which was inaugurated in 1904. The headquarters of the HHLA Group came up with this name because its cornices, oriels and decorative elements looked almost palatial. ‘Bei St. Annen 1’ was joined to the adjacent warehouses in 2001/2002 by the award-winning architectural practice gmp (von Gerkan, Marg and Partners). They combined modern offices, meeting rooms and lifts with historic beams and staircases. Since the conversion, a striking glass roof curves over the formerly open atrium.

Hälssen and Lyon moved into an office and warehouse building in 1887, which remains the headquarters of the famous tea company to this day.

300,000

square metres of space are now rented out by HHLA in the Speicherstadt.

Quartiersleute

then and now

read more

Hamburger Hafen und Logistik Aktiengesellschaft

Bei St. Annen 1

20457 Hamburg

Phone +49 40 3088-0

www.hhla.de/en

Responsible in terms of the German press law

Carolin Flemming, Head of Corporate Communications

→ Write e-mail

Editor in chief

Christian Lorenz

Photo credits

Adobe Stock, hamburger-fotoarchiv.de, Thomas Hampel, Hälssen & Lyon / Zitzlaff, HHLA, Georg Koppmann, Archiv Egbert Kossak, Nele Martensen, Thies Rätzke, Gustav Werbeck, Wikipedia